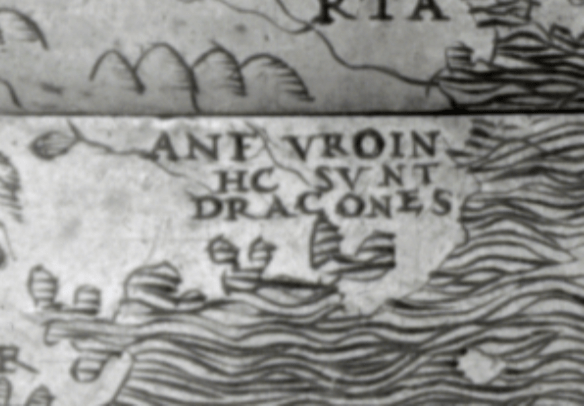

It’s hard to imagine a time before GPS and Google Maps, even back before the days of those AAA maps for long car rides. But before automobiles and trains or Trans-Atlantic flight, cartography was as much a mystery as it was science. In 150, Ptolemy’s Geographia warned of mythical characters that roamed terra ignota, or “lands unknown.” Later, and up through the 1500s, the Hunt-Lenox Globe, the most complete of its time, marked unknown areas with the Latin phrase “HC SVNT DRACONES,” or “here be dragons” near the coast of eastern Asia.

While cartography has improved tremendously in the last several hundred years, our fear of the unknown persists. In this current crisis at the dawn of a new decade, we continue to face down our own dragons of uncertainty.

Knightian Uncertainty

In 1921, the economist Frank Knight distinguished between risk and uncertainty. He wrote:

There is a fundamental distinction between the reward for taking a known risk and that for assuming a risk whose value is not known. A known risk is easily converted into an effective certainty. While true uncertainty is not susceptible to measurement.

Put simply, he argues that risk (for which probabilities are known) is different from true uncertainty (for which probability is not known). True uncertainty, or Knightian uncertainty occurs when we have no knowledge and/or no way of knowing future events. This creates a gap of information between what we do know and what we need to know to make decisions.

As nonprofit practitioners, it is essential to distinguish between how to deal with risk and uncertainty as well. While we often conflate risk and uncertainty, it is important to distinguish these two notions before delving into the actions nonprofits should undertake in these challenging times.

- Our decision-making depends on it. Whether we have to deal with risk which is probabilistically measured or true uncertainty (Knightian uncertainty) where it cannot, will determine what policies or practices we undertake and how we go about making those decision. In a Knightian setting, our intuitions regarding trends or sensing pending change will not be manifested in data.

- Our survival depends on it. Every action undertaken at any time carries some measure of risk in some environment of uncertainty. However, as uncertainty rises, we tend to be more risk averse even when the data argues against such an approach. Many nonprofits are facing an existential crisis (as are several funders). The decisions we make today will determine whether we survive tomorrow. Survival, however that is construed, is a function of making the next right choice. For context, it is important to remember that the average lifespan of a Fortune 500 company used to be 75 years. Today, it’s less than 25 years. Survival may look different than what we anticipate.

Innovation Loves a Crisis

When Jong-Yong Yun became the CEO of Samsung, he built a culture of “perpetual crisis,” which for its merits and detractors, has become the world’s largest consumer electronics company. He reminds his team regularly of the disasters around the corner such as market implosions and Chinese competitiveness.

When a boat is sinking, it is important to plug the leak. And so, it is common in a crisis for nonprofits to rush to austerity, moving directly to cost cutting. This is a wise first step but obviously can curtail innovation both in the short and long run. The next urgent question, once the leaks are sealed, is to turn to the business model of the nonprofit and assess its weakness and instability. Paul J.H. Schoemaker, research director at the Mack Center for Technological Innovation reminds us that this, “in turn, can lead to restructuring and reinvention.” He goes on to caution against reliance on incremental innovation instead of the much-needed transformative innovation. “The largest gains…come from more daring innovations that challenge the paradigm and the organization,” Schoemaker says.

Disruptive innovation can often be seen as a buzz word in corporate circles. However, it is far too common to see nonprofits retreat to minor repairs of flawed systems rather than embracing wholesale innovation. There’s a balance somewhere between a constant state of crisis and embracing the chaos we are currently experiencing to see the probabilistic opportunities for change, growth, and impact.

A New Map

“Almost all innovation happens by making connections between fields that other people don’t realize.” – Robert Lang

Innovation is closer than you think but your old maps will not help you find it. Today, you can take your strategic plan and your fundraising plan and put it to better use – as toilet paper. None of your current plans will be effective in charting the new waters we collectively face. That new map is about info-filling, adding as many details about your subsector, what’s happening in other sectors, what is happening in the larger economy, and globally to close the distance between what you know and what you need to know.

For far too long, nonprofits have left everything besides relationships and their services out of their thinking. Even when it comes to the evidence-based body of knowledge on fundraising practices, we “go back to our knitting,” according to Wharton management professor Mary Benner.

Nonprofit innovation should borrow a page from Google’s playbook.

- Innovation comes from anywhere: don’t privilege innovation activities at the top or as a side project. Everyone inside and outside your organization can be a source of innovation.

- Focus on the beneficiary: notice I didn’t say donor. Presumably, you’ve made it easy and convenient for a donor to make a gift. However, recall the admonition of Tom Ahern: “donors don’t give to you, they give through you.” Reminding donors of the cause they care about, not the organizational need, will focus your attention on your innovative ideas.

- Aim to be 10x better: embracing incremental change is the worst sin an organization can be guilty of at this stage. If you come to the table trying to figure out how to get $50,000 to maintain payroll, you are doomed to repeat that task in perpetuity. Figure out a way to raise $500,000.

- Bet on technical insights: you have information at your fingertips about donors and your organization, your subsector, and most importantly what works and what doesn’t even outside your organization. You already have the tools to see the problems ahead and to fix them.

- Ship and iterate: there’s a danger that also lurks in every nonprofit hallway that is “we’ve only got one shot at this” and “we’ve got to have this perfect.” Rather, embrace the Google (and Facebook) approach of “done is better than perfect.” If you’re worried about mistakes, invite funders to help co-create the next solutions and involve volunteers more deeply in your work at every level.

- Give your staff 20% time: it doesn’t need to rigidly be 20% but give everyone the opportunity to spend time thinking, reading, or working on a project they are passionate about even if it’s outside their core job description. These are the way that people bring new insights and opportunities to the table.

- Default to open processes: Invite others to engage in ways to make any process in your organization better. “It’s not my department” is anathema to a healthy improving ecosystem especially now.

- Fail well: this isn’t just forgiving failure, it is fully expecting some projects to fail. Celebrate failures and fund them, even in a time of austerity. Our failures are the lessons we learn and help us get better for the future.

An Old GPS

There are actually nine principles from Google but the last one is: “Have a Mission that Matters.” I have no doubt that everyone reading this has a mission. I wonder if it’s a mission that matters. Does it matter to everyone at the organization and does it drive them waking up in the morning?

I’m originally from Minnesota, the North Star state, so it came as no surprise to me to discover that ancient seafarers used the star, Polaris, to guide their ships especially through uncharted waters. I was surprised to learn that Polaris only points true north twice a day. When they didn’t have a guide, they trusted their training and one another to keep them on the right course.

Sometimes, it seems as though we are adrift in an ocean that gets scarier every day. Our north star is a mission that matters and in nearly every case, that mission has no end. We will continue fighting disease and discrimination, protecting animals and the arts long after these turbulent waters subside.

Your work is important and so are you. We are all on this boat together and we’ll all get safely to the shore together.